Scared-4-America is a blog for political, social commentary, and economic discussions. Scared4America believes in reading, questioning, and speaking truth to power.

7.31.2009

7.30.2009

Republican Racist Agenda

Visit msnbc.com for Breaking News, World News, and News about the Economy

This is how we let the credit crunch happen, Ma'am ...

Queen told how economists missed financial crisis

The Queen has been sent a letter by a group of eminent economists explaining how "financial wizards" failed to "foresee the timing, extent and severity" of the economic crisis, it was reported. The Financial Times reported, There is nothing like a monarch’s pointed question to make the great and good squirm. Queen Elizabeth stumped her hosts at the London School of Economics by asking why no one had seen the financial crisis coming. Scholars at that and other universities should feel the sting: if they cannot be counted on to spot dangers to the economy, why have economists at all?

The Financial Times reported, There is nothing like a monarch’s pointed question to make the great and good squirm. Queen Elizabeth stumped her hosts at the London School of Economics by asking why no one had seen the financial crisis coming. Scholars at that and other universities should feel the sting: if they cannot be counted on to spot dangers to the economy, why have economists at all?

Some of Britain’s leading economic experts have now sent the Queen a reply. They point out that some did foresee the crisis, prominent economists included. What failed was the “collective imagination of many bright people”.

More can be said. The economics profession’s obliviousness to imminent collapse has led it to search whatever soul it may have to learn where it went astray. A prime suspect is a theory too optimistic about the rationality of people’s choices and the possibility of capturing them in mathematics.

The truth may be simpler and more depressing: that no economic theory can perform the feats its users have come to expect of it. Economics is unlikely ever to be very good at predicting the future. Too much of what happens in an economy depends on what people expect to happen. Even state-of-the-art forecasts are therefore better guides to the present mood than the future. though they may also be self-fulfilling prophecies.

Dabbling in paradox limits the use of economics as a practical guide. Today the profession’s best advice must convince politicians and the public to combat a crisis born of insufficient thrift by a recourse to record borrowing. Those who saw danger had no easier task: even reminding people of gravity’s existence is a hard sell when everything is going up.

If predictions of physics-like precision are in demand, they will be supplied. Collective delusion must therefore be blamed as much on the consumers of economics – companies, investors, the media – as its producers. But its irresponsible use does not mean economics is useless. It is rather good at explaining the past and guessing unintended consequences of well-meaning policies – invaluable tools for cleaning up financial markets.

So we do need economists in public debate, but ones not blinded by mathematical sophistication or paradoxes beyond the lay public’s grasp. The public intellectual’s virtues – curiosity about other fields, aversion to dogma – could do the discipline much good. Unfortunately these are no longer much valued in the academic hierarchy. University presidents should perhaps take up Her Majesty’s query.

The Queen has been sent a letter by a group of eminent economists explaining how "financial wizards" failed to "foresee the timing, extent and severity" of the economic crisis, it was reported.

The Financial Times reported, There is nothing like a monarch’s pointed question to make the great and good squirm. Queen Elizabeth stumped her hosts at the London School of Economics by asking why no one had seen the financial crisis coming. Scholars at that and other universities should feel the sting: if they cannot be counted on to spot dangers to the economy, why have economists at all?

The Financial Times reported, There is nothing like a monarch’s pointed question to make the great and good squirm. Queen Elizabeth stumped her hosts at the London School of Economics by asking why no one had seen the financial crisis coming. Scholars at that and other universities should feel the sting: if they cannot be counted on to spot dangers to the economy, why have economists at all?Some of Britain’s leading economic experts have now sent the Queen a reply. They point out that some did foresee the crisis, prominent economists included. What failed was the “collective imagination of many bright people”.

More can be said. The economics profession’s obliviousness to imminent collapse has led it to search whatever soul it may have to learn where it went astray. A prime suspect is a theory too optimistic about the rationality of people’s choices and the possibility of capturing them in mathematics.

The truth may be simpler and more depressing: that no economic theory can perform the feats its users have come to expect of it. Economics is unlikely ever to be very good at predicting the future. Too much of what happens in an economy depends on what people expect to happen. Even state-of-the-art forecasts are therefore better guides to the present mood than the future. though they may also be self-fulfilling prophecies.

Dabbling in paradox limits the use of economics as a practical guide. Today the profession’s best advice must convince politicians and the public to combat a crisis born of insufficient thrift by a recourse to record borrowing. Those who saw danger had no easier task: even reminding people of gravity’s existence is a hard sell when everything is going up.

If predictions of physics-like precision are in demand, they will be supplied. Collective delusion must therefore be blamed as much on the consumers of economics – companies, investors, the media – as its producers. But its irresponsible use does not mean economics is useless. It is rather good at explaining the past and guessing unintended consequences of well-meaning policies – invaluable tools for cleaning up financial markets.

So we do need economists in public debate, but ones not blinded by mathematical sophistication or paradoxes beyond the lay public’s grasp. The public intellectual’s virtues – curiosity about other fields, aversion to dogma – could do the discipline much good. Unfortunately these are no longer much valued in the academic hierarchy. University presidents should perhaps take up Her Majesty’s query.

7.29.2009

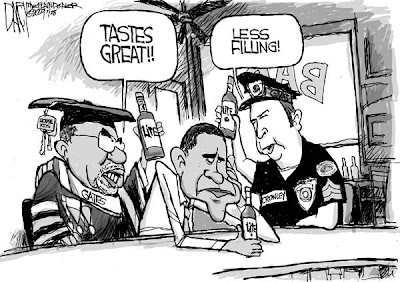

A Man's Home Is His Constitutional Castle

Amendment IV

Amendment IVThe right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

In Slate the article "A Man's Home Is His Constitutional Castle: Henry Louis Gates Jr. should have taken his stand on the Bill of Rights, not on his epidermis or that of the arresting officer"Christopher Hitchens writes, "There are the things you can try when confronted by a cop, and there are the things that you can't—or had better not. Last Memorial Day, I was going in a taxi down to Washington, D.C.'s Vietnam Memorial when a police car cut across the traffic and slammed everything to a halt. Opening the window and asking what the problem was and how long it might last, I was screeched at by a stringy-haired, rat-faced blond beast, who acted as if she had been waiting all year for the chance to hurt someone. (She was wearing a uniform that I had helped pay for.) I often have a hard time keeping my trap shut, but I saw at once that this damaged creature was aching for trouble and that it would cost me days rather than hours if I supplied her with any back chat. (I think it was the mad way she yelled, "Because I can!" and "Because I say so!") She was so avid with hatred that I didn't even try to get close enough to ask or see her name or number. The whole thing, especially my own ignoble passivity, gnaws at me still when I reflect upon it. But it didn't, if you understand me, reinforce any humiliating folk memory. Indeed, I had more or less forgotten it until recently."

In Slate the article "A Man's Home Is His Constitutional Castle: Henry Louis Gates Jr. should have taken his stand on the Bill of Rights, not on his epidermis or that of the arresting officer"Christopher Hitchens writes, "There are the things you can try when confronted by a cop, and there are the things that you can't—or had better not. Last Memorial Day, I was going in a taxi down to Washington, D.C.'s Vietnam Memorial when a police car cut across the traffic and slammed everything to a halt. Opening the window and asking what the problem was and how long it might last, I was screeched at by a stringy-haired, rat-faced blond beast, who acted as if she had been waiting all year for the chance to hurt someone. (She was wearing a uniform that I had helped pay for.) I often have a hard time keeping my trap shut, but I saw at once that this damaged creature was aching for trouble and that it would cost me days rather than hours if I supplied her with any back chat. (I think it was the mad way she yelled, "Because I can!" and "Because I say so!") She was so avid with hatred that I didn't even try to get close enough to ask or see her name or number. The whole thing, especially my own ignoble passivity, gnaws at me still when I reflect upon it. But it didn't, if you understand me, reinforce any humiliating folk memory. Indeed, I had more or less forgotten it until recently." More recently, I was walking at night in the wooded California suburb where I spend the summer, trying to think about an essay I was writing. Suddenly, a police cruiser was growling quietly next to me and shining a light. "What are you doing?" I don't know quite what it was—I'd been bored and delayed that week at airport security—but I abruptly decided that I was in no mood, so I responded, "Who wants to know?" and continued walking. "Where do you live?" said the voice. "None of your business," said I. "What's under your jacket?" "What's your probable cause for asking?" I was now almost intoxicated by my mere possession of constitutional rights. There was a pause, and then the cop asked almost pleadingly how he was to know if I was an intruder or burglar, or not. "You can't know that," I said. "It's for me to know and for you to find out. I hope you can come up with probable cause." The car gurgled alongside me for a bit and then pulled away. No doubt the driver then ran some sort of check, but he didn't come back.

More recently, I was walking at night in the wooded California suburb where I spend the summer, trying to think about an essay I was writing. Suddenly, a police cruiser was growling quietly next to me and shining a light. "What are you doing?" I don't know quite what it was—I'd been bored and delayed that week at airport security—but I abruptly decided that I was in no mood, so I responded, "Who wants to know?" and continued walking. "Where do you live?" said the voice. "None of your business," said I. "What's under your jacket?" "What's your probable cause for asking?" I was now almost intoxicated by my mere possession of constitutional rights. There was a pause, and then the cop asked almost pleadingly how he was to know if I was an intruder or burglar, or not. "You can't know that," I said. "It's for me to know and for you to find out. I hope you can come up with probable cause." The car gurgled alongside me for a bit and then pulled away. No doubt the driver then ran some sort of check, but he didn't come back. In the first instance, I found again what everyone knows, which is that there are a lot of warped misfits and inadequates who are somehow allowed to join the police force. In the second instance, I found that a good cop even at dead of night can and will use his judgment, even if the "suspect" is being a slight pain in the ass. But seriously, do you think I could have pulled the second act, or would even have tried it, or been given the chance to try it, if I had been black? The "Skip" Gates question is determined just as much by what can't and what doesn't happen as it is by what regularly does. (Colbert I. King of the Washington Post once wrote a very telling column about how his parents instilled in him the need for punctuality. The underlining of their everyday lesson was that if you were late, you might have to run, and a young black man racing through the streets could well be detained before he reached his lawful destination.)

In the first instance, I found again what everyone knows, which is that there are a lot of warped misfits and inadequates who are somehow allowed to join the police force. In the second instance, I found that a good cop even at dead of night can and will use his judgment, even if the "suspect" is being a slight pain in the ass. But seriously, do you think I could have pulled the second act, or would even have tried it, or been given the chance to try it, if I had been black? The "Skip" Gates question is determined just as much by what can't and what doesn't happen as it is by what regularly does. (Colbert I. King of the Washington Post once wrote a very telling column about how his parents instilled in him the need for punctuality. The underlining of their everyday lesson was that if you were late, you might have to run, and a young black man racing through the streets could well be detained before he reached his lawful destination.) I can easily see how a black neighbor could have called the police when seeing professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. trying to push open the front door of his own house. And I can equally easily visualize a thuggish or oversensitive black cop answering the call. And I can also see how long it might take the misunderstanding to dawn on both parties. But Gates has a limp that partly accounts for his childhood nickname and is slight and modest in demeanor. Moreover, whatever he said to the cop was in the privacy of his own home. It is monstrous in the extreme that he should in that home be handcuffed, and then taken downtown, after it had been plainly established that he was indeed the householder. The president should certainly have kept his mouth closed about the whole business—he is a senior law officer with a duty of impartiality, not the micro-manager of our domestic disputes—but once he had said that the police conduct was "stupid," he ought to have stuck to it, quite regardless of the rainbow of shades that was so pathetically and opportunistically deployed by the Cambridge Police Department. It is the U.S. Constitution, and not some competitive agglomeration of communities or constituencies, that makes a citizen the sovereign of his own home and privacy. There is absolutely no legal requirement to be polite in the defense of this right. And such rights cannot be negotiated away over beer.

I can easily see how a black neighbor could have called the police when seeing professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. trying to push open the front door of his own house. And I can equally easily visualize a thuggish or oversensitive black cop answering the call. And I can also see how long it might take the misunderstanding to dawn on both parties. But Gates has a limp that partly accounts for his childhood nickname and is slight and modest in demeanor. Moreover, whatever he said to the cop was in the privacy of his own home. It is monstrous in the extreme that he should in that home be handcuffed, and then taken downtown, after it had been plainly established that he was indeed the householder. The president should certainly have kept his mouth closed about the whole business—he is a senior law officer with a duty of impartiality, not the micro-manager of our domestic disputes—but once he had said that the police conduct was "stupid," he ought to have stuck to it, quite regardless of the rainbow of shades that was so pathetically and opportunistically deployed by the Cambridge Police Department. It is the U.S. Constitution, and not some competitive agglomeration of communities or constituencies, that makes a citizen the sovereign of his own home and privacy. There is absolutely no legal requirement to be polite in the defense of this right. And such rights cannot be negotiated away over beer. Race or color are second-order considerations in this, if they are considerations at all. I was once mugged by a white man on the Lower East Side of New York, and then, having given my evidence, was laboriously shown a whole photo album of black "perps" at the local station house. The absurdity of the exercise lay not just in the inability of a half-trained and uncultured force to believe what I was telling them, but in the certainty that their stupidity was helping the guilty party to make a getaway. Professor Gates should have taken his stand on the Bill of Rights and not on his epidermis or that of the arresting officer, and, if he didn't have the presence of mind to do so, that needn't inhibit the rest of us.

Race or color are second-order considerations in this, if they are considerations at all. I was once mugged by a white man on the Lower East Side of New York, and then, having given my evidence, was laboriously shown a whole photo album of black "perps" at the local station house. The absurdity of the exercise lay not just in the inability of a half-trained and uncultured force to believe what I was telling them, but in the certainty that their stupidity was helping the guilty party to make a getaway. Professor Gates should have taken his stand on the Bill of Rights and not on his epidermis or that of the arresting officer, and, if he didn't have the presence of mind to do so, that needn't inhibit the rest of us.

Labels:

Christopher Hitchens,

Mama Voted for Obama,

Race,

Skip Gates,

Slate

7.24.2009

Bill Moyers sits down with Bill Black

The financial industry brought the economy to its knees, but how did they get away with it? With the nation wondering how to hold the bankers accountable, Bill Moyers sits down with Bill Black, the former senior regulator who cracked down on banks during the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s. Black offers his analysis of what went wrong and his critique of the bailout. This show aired April 3, 2009. Bill Moyers Journal airs Fridays at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings). For more: http://www.pbs.org/billmoyers

7.21.2009

Molly Ivins: The Suicide of Capitalism

Jul 17, 2006

By Molly Ivins

AUSTIN, Texas—In case you haven’t got anything else to worry about—like war in the Middle East, nuclear showdowns, global warming or Apocalypse Now—how about the suicide of capitalism?

Late last month, the U.S. Court of Appeals struck down a new rule by the Securities and Exchange Commission requiring mandatory registration with the SEC for most hedge funds. This may not strike you as the end of the world, but that’s because you’ve either forgotten what a hedge fund is or how much trouble the funds can get us into.

These investment pools for rich folks are now a $1.2-trillion industry (known to insiders, I am pleased to report, as “the hedge fund community”). Hedge funds are now beginning to be used by average investors and pension investors. Back in 1998, there was this little-bitty old hedge fund called Long Term Capital Management. Because hedge funds make high-risk bets, Long Term Capital got itself in so much trouble its collapse actually threatened to wreck world markets, and regulators had to step in to negotiate a $3.6-billion bailout. A similar fiasco at this point probably would break world markets.

By Molly Ivins

AUSTIN, Texas—In case you haven’t got anything else to worry about—like war in the Middle East, nuclear showdowns, global warming or Apocalypse Now—how about the suicide of capitalism?

Late last month, the U.S. Court of Appeals struck down a new rule by the Securities and Exchange Commission requiring mandatory registration with the SEC for most hedge funds. This may not strike you as the end of the world, but that’s because you’ve either forgotten what a hedge fund is or how much trouble the funds can get us into.

These investment pools for rich folks are now a $1.2-trillion industry (known to insiders, I am pleased to report, as “the hedge fund community”). Hedge funds are now beginning to be used by average investors and pension investors. Back in 1998, there was this little-bitty old hedge fund called Long Term Capital Management. Because hedge funds make high-risk bets, Long Term Capital got itself in so much trouble its collapse actually threatened to wreck world markets, and regulators had to step in to negotiate a $3.6-billion bailout. A similar fiasco at this point probably would break world markets.

The Securities and Exchange Commission under William Donaldson (appointed after the Enron mess) had tried to regulate hedge funds. But Christopher Cox, current SEC chairman and no friend of regulation, said he would consult other members of the administration about whether to appeal the ruling, which “came on the same day as disclosures,” reports The Washington Post, that the feds “are investigating Pequot Capital Management, Inc., a $7 billion hedge fund, for possible insider trading.” Nice timing, judges.

The Securities and Exchange Commission under William Donaldson (appointed after the Enron mess) had tried to regulate hedge funds. But Christopher Cox, current SEC chairman and no friend of regulation, said he would consult other members of the administration about whether to appeal the ruling, which “came on the same day as disclosures,” reports The Washington Post, that the feds “are investigating Pequot Capital Management, Inc., a $7 billion hedge fund, for possible insider trading.” Nice timing, judges.This is the third time in less than a year the appeals court has blocked the SEC from acting beyond its authority. According to The Washington Post, “Former SEC member Harvey J. Goldschmid, who voted to approve the plan, yesterday urged regulators to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, members of Congress or both. In the Pequot case, a former SEC lawyer who worked on the Pequot investigation before being fired by the agency has written a letter to key members of the Senate banking and finance committees alleging that the SEC dropped the probe because of political pressure.” The lawyer said he was prevented by political pressure from interviewing a top Wall Street executive. Sources said the executive was John J. Mack, once chairman of Pequot and now chief executive of Morgan Stanley—and a major fundraiser for President Bush’s campaigns. I’d say the guy’s wired.

So what we have here is yet another case of ideological decision-making (“all government regulation is bad”) being applied despite the most obvious promptings of common sense. Come to think of it, that’s exactly the pattern this administration has followed with war in the Middle East, nuclear showdowns, global warming and Apocalypse Now.

Well, if the administration won’t do something, how about Congress? Reps. Barney Frank, Michael Capuano and Paul Kanjorski are co-sponsoring a bill to reverse the court decision—and to gather more information about how hedge funds affect the economy. This would seem a peppy response, except Congress seems quite determined to do nothing at all these days, having already beaten the record of the “do-nothing Congress” of the Truman era. As near as can be figured out, the Republican “game plan” is to do absolutely nothing between now and November. This doesn’t improve anyone’s opinion of the Republican Congress, but has the happy effect of dragging the Democrats down with them.

7.20.2009

Vintage Molly Ivins (Oct. 1999)

We certainly miss you, Molly Ivins. Yet, you still speak to us from the grave. Below is a column written by Ms. Ivins back in October 26, 1999. She was one of the good guys in this financial debacle. Read her words and weep for our nation that elected Bush and his merry band of Wall Street, banker, finance and insurance pirates. They've looted our nation's treasury right before our very eyes.

Don't believe the hype from all of the goofball journalists and pundits as well as the blindsided politicians that now clearly see the implosion of our financial/economic/banking system as it melts away. There were clear lucid voices that were like the Prophet Jeremiah crying in the wilderness for some sanity. But, in a positively Orwellian world, the free market capitalists killed capitalism with their unquenchable greed.

Don't believe the hype from all of the goofball journalists and pundits as well as the blindsided politicians that now clearly see the implosion of our financial/economic/banking system as it melts away. There were clear lucid voices that were like the Prophet Jeremiah crying in the wilderness for some sanity. But, in a positively Orwellian world, the free market capitalists killed capitalism with their unquenchable greed.

By Molly Ivins: AUSTIN, Texas — I feel vaguely like Henry Higgins in "My Fair Lady," announcing with gleefully inhumane relish: "She'll regret it, she'll regret it! Ha!"

"I can see her now, Mrs. Freddy Eynsford-Hill, in a wretched little flat above the store!

"I can see her now, not a penny in the till, and the bill collectors knocking at the door!"

Which is to say, the new banking bill is a thoroughly lousy idea, and the party most likely to regret it is us.

The 1999 Gramm-Leach Act is about to replace the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act, with the result that bankers, brokers and insurance companies can all get into one another's business. It's a done deal except for the final vote on the conference-committee agreement. The inevitable result will be a wave of mergers creating gigantic financial entities.

In a stupefying moment of pomposity, a New York Times editorial solemnly concluded: "The principle of freer competition is the economic engine of this era. But the other imperative is to demand openness, financial prudence and safeguards so that the vast new concentrations of wealth and power do not create new abuses." When was the last time you saw a vast concentration of wealth and power that DIDN'T create abuses?

Or as Sen. Richard Bryan of Nevada so neatly put it, "Industry has gotten a gold mine while the American public has gotten the shaft."

Just to remind you one more time of how corrupt our political system is (and members of the Senate had a cow when Sen. John McCain used the word "corrupt" to describe the campaign-financing system a few weeks ago), the financial industry has poured more than $30 million in soft money, PAC and individual contributions to politicians in 1999, 60 percent to the Republicans. That's just over one-third of the amount spent during the entire 1997-98 election cycle, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

And this certainly qualifies as responsive politics. So much money has gone into getting this bill passed during the last 10 years that there is no hope of stopping it.

The only thing that held it up this long was Sen. Phil Gramm's stubborn insistence on making it worse. He wanted to use the occasion to gut the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, which forces banks to make loans in the same area where they take in deposits — in other words, to quit red-lining their own customers. Most of CRA was saved by the White House.

But the bad news is:

— Privacy: What's in the bill doesn't protect your financial privacy worth a rat's heinie. In theory, the new law says that banks have to disclose their privacy policies. That doesn't mean they always have to protect your privacy, or give you an opt-out before selling your information to every telemarketer on earth.

Ever use a check at a liquor store? Do you smoke? Ever put something from Victoria's Secret on your credit card? Take any meds? Ever see a shrink? (Actually, that's increasingly less likely under our dandy system of corporate HMO health care.) The health information you provided to your life insurer will be passed along to your banker when you go to get a mortgage and will help determine the interest rate you get charged, as will your lifestyle info.

— Natural disaster: In theory, banks that merge with insurance companies are obliged to put themselves at only limited risk if some catastrophic event threatens their insurance subsidiary.

What's the only business in the world that takes global warming seriously? Insurance.

We just watched a third of North Carolina go under water. All the global warming experts think that increased hurricanes are one consequence of the phenomenon: One Mitch slams straight into Miami or Savannah, and the entire industry will stagger. Think it won't affect the banks that own it?

— Unnatural disaster: Don't get me started on the evidence for my theory that bankers are among the stupidest people on God's green earth. These are the geniuses who loaned all that money to Latin America in the '80s and then had to write it off. This is the system that almost collapsed last year because one hedge fund spiraled out of control — and had to be bailed out by the Fed. These are the clever fellows who didn't notice their banks were being used to launder Russian mafia money.

"Too Big to Fail" will be the new order of the day. And guess who gets left holding the bag when they're too big to fail? One of these monsters goes down, and it will cost as much as the whole S&L debacle.

Alan Greenspan, not heretofore associated with the populist left, told bankers in a speech two weeks ago that the bill will create a class of super-institutions Too Big to Fail. In his usual impenetrable linguistic style, he allowed as how some new form of supervision will have to be created, but the regulators are well behind the financial system.

— Consumers: Phil Gramm promises us that increased competition will bring about a wonderful world of dandy new services at lower prices. Not a single soul thinks this bill will do anything but cause a tidal wave of mergers and acquisitions, leaving us with fewer options than ever. We'll get fewer and more powerful institutions with the ability to overcharge for products because of their market share.

Ed Mierzwinkski of Public Interest Research says the only customers whom banks care about are other banks' customers. The only offers you get for those 3 percent APR credit cards come from other banks. Once you sign up, the banks suddenly announce that the offer is time-limited.

— Most obscure horrible provision in bill: Rep. Thomas Bliley of Virginia stuck in a $95 billion give-away for insurance. The trend in that industry is "de-mutualization," a mutual being a entity where the rate-payers own the company. If the company "de-mutualizes" by going to a stockholder-owned mutual holding company, without compensation to the policy-holder owners, the increased value of the company goes not to the former owners but to execs with big stock options and new shareholders. The former owners lose equity of an average $1,700 each, according to the Center for Insurance Research in Cambridge, Mass.

Twenty-seven states have either rejected or have not enacted mutual holding company conversion laws. Hiya, sucker.

"I can see her now, Mrs. Freddy Eynsford-Hill, in a wretched little flat above the store!

"I can see her now, not a penny in the till, and the bill collectors knocking at the door!"

Which is to say, the new banking bill is a thoroughly lousy idea, and the party most likely to regret it is us.

The 1999 Gramm-Leach Act is about to replace the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act, with the result that bankers, brokers and insurance companies can all get into one another's business. It's a done deal except for the final vote on the conference-committee agreement. The inevitable result will be a wave of mergers creating gigantic financial entities.

In a stupefying moment of pomposity, a New York Times editorial solemnly concluded: "The principle of freer competition is the economic engine of this era. But the other imperative is to demand openness, financial prudence and safeguards so that the vast new concentrations of wealth and power do not create new abuses." When was the last time you saw a vast concentration of wealth and power that DIDN'T create abuses?

Or as Sen. Richard Bryan of Nevada so neatly put it, "Industry has gotten a gold mine while the American public has gotten the shaft."

Just to remind you one more time of how corrupt our political system is (and members of the Senate had a cow when Sen. John McCain used the word "corrupt" to describe the campaign-financing system a few weeks ago), the financial industry has poured more than $30 million in soft money, PAC and individual contributions to politicians in 1999, 60 percent to the Republicans. That's just over one-third of the amount spent during the entire 1997-98 election cycle, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

And this certainly qualifies as responsive politics. So much money has gone into getting this bill passed during the last 10 years that there is no hope of stopping it.

The only thing that held it up this long was Sen. Phil Gramm's stubborn insistence on making it worse. He wanted to use the occasion to gut the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, which forces banks to make loans in the same area where they take in deposits — in other words, to quit red-lining their own customers. Most of CRA was saved by the White House.

But the bad news is:

— Privacy: What's in the bill doesn't protect your financial privacy worth a rat's heinie. In theory, the new law says that banks have to disclose their privacy policies. That doesn't mean they always have to protect your privacy, or give you an opt-out before selling your information to every telemarketer on earth.

Ever use a check at a liquor store? Do you smoke? Ever put something from Victoria's Secret on your credit card? Take any meds? Ever see a shrink? (Actually, that's increasingly less likely under our dandy system of corporate HMO health care.) The health information you provided to your life insurer will be passed along to your banker when you go to get a mortgage and will help determine the interest rate you get charged, as will your lifestyle info.

— Natural disaster: In theory, banks that merge with insurance companies are obliged to put themselves at only limited risk if some catastrophic event threatens their insurance subsidiary.

What's the only business in the world that takes global warming seriously? Insurance.

We just watched a third of North Carolina go under water. All the global warming experts think that increased hurricanes are one consequence of the phenomenon: One Mitch slams straight into Miami or Savannah, and the entire industry will stagger. Think it won't affect the banks that own it?

— Unnatural disaster: Don't get me started on the evidence for my theory that bankers are among the stupidest people on God's green earth. These are the geniuses who loaned all that money to Latin America in the '80s and then had to write it off. This is the system that almost collapsed last year because one hedge fund spiraled out of control — and had to be bailed out by the Fed. These are the clever fellows who didn't notice their banks were being used to launder Russian mafia money.

"Too Big to Fail" will be the new order of the day. And guess who gets left holding the bag when they're too big to fail? One of these monsters goes down, and it will cost as much as the whole S&L debacle.

Alan Greenspan, not heretofore associated with the populist left, told bankers in a speech two weeks ago that the bill will create a class of super-institutions Too Big to Fail. In his usual impenetrable linguistic style, he allowed as how some new form of supervision will have to be created, but the regulators are well behind the financial system.

— Consumers: Phil Gramm promises us that increased competition will bring about a wonderful world of dandy new services at lower prices. Not a single soul thinks this bill will do anything but cause a tidal wave of mergers and acquisitions, leaving us with fewer options than ever. We'll get fewer and more powerful institutions with the ability to overcharge for products because of their market share.

Ed Mierzwinkski of Public Interest Research says the only customers whom banks care about are other banks' customers. The only offers you get for those 3 percent APR credit cards come from other banks. Once you sign up, the banks suddenly announce that the offer is time-limited.

— Most obscure horrible provision in bill: Rep. Thomas Bliley of Virginia stuck in a $95 billion give-away for insurance. The trend in that industry is "de-mutualization," a mutual being a entity where the rate-payers own the company. If the company "de-mutualizes" by going to a stockholder-owned mutual holding company, without compensation to the policy-holder owners, the increased value of the company goes not to the former owners but to execs with big stock options and new shareholders. The former owners lose equity of an average $1,700 each, according to the Center for Insurance Research in Cambridge, Mass.

Twenty-seven states have either rejected or have not enacted mutual holding company conversion laws. Hiya, sucker.

Molly Ivins is a columnist for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram

Jim Rogers on CNBC: March 12, 2008

"How much money does the Federal Reserve have?" Rogers asks. "I know they can run their printing presses forever, but that is not good for the world, inflation is not good for the world, a collapsing currency is not good for the world. It means worse recession in the end."

The Old Titans All Collapsed. Is the U.S. Next?

Back in August, during the panic over mortgages, Alan Greenspan offered reassurance to an anxious public. The current turmoil, the former Federal Reserve Board chairman said, strongly resembled brief financial scares such as the Russian debt crisis of 1998 or the U.S. stock market crash of 1987. Not to worry.

Back in August, during the panic over mortgages, Alan Greenspan offered reassurance to an anxious public. The current turmoil, the former Federal Reserve Board chairman said, strongly resembled brief financial scares such as the Russian debt crisis of 1998 or the U.S. stock market crash of 1987. Not to worry.But in the background, one could hear the groans and feel the tremors as larger political and economic tectonic plates collided. Nine months later, Greenspan's soothing analogies no longer wash. The U.S. economy faces unprecedented debt levels, soaring commodity prices and sliding home prices, to say nothing of a weak dollar. Despite the recent stabilization of the economy, some economists fear that the world will soon face the greatest financial crisis since the 1930s.

That analogy is hardly a perfect fit; there's almost no chance of another sequence like the Great Depression, where the stock market dove 80 percent, joblessness reached 25 percent, and the Great Plains became a dustbowl that forced hundreds of thousands of "Okies" to flee to California. But Americans should worry that the current unrest betokens the sort of global upheaval that upended previous leading world economic powers, most notably Britain.

More than 80 percent of Americans now say that we are on the wrong track, but many if not most still believe that the history of other nations is irrelevant -- that the United States is unique, chosen by God. So did all the previous world economic powers: Rome, Spain, the Netherlands (in the maritime glory days of the 17th century, when New York was New Amsterdam) and 19th-century Britain. Their early strength was also their later weakness, not unlike the United States since the 1980s.

There is a considerable literature on these earlier illusions and declines. Reading it, one can argue that imperial Spain, maritime Holland and industrial Britain shared a half-dozen vulnerabilities as they peaked and declined: a sense of things no longer being on the right track, intolerant or missionary religion, military or imperial overreach, economic polarization, the rise of finance (displacing industry) and excessive debt. So too for today's United States.

Before we amplify the contemporary U.S. parallels, the skeptic can point out how doomsayers in each nation, while eventually correct, were also premature. In Britain, for example, doubters fretted about becoming another Holland as early as the 1860s, and apprehension surged again in the 1890s, based on the industrial muscle of such rivals as Germany and the United States. By the 1940s, those predictions had come true, but in practical terms, the critics of the 1860s and 1890s were too early.

Premature fears have also dogged the United States. The decades after the 1968 election were marked by waves of a new national apprehension: that U.S. post-World War II global hegemony was in danger. The first, in 1968-72, involved a toxic mix of global trade and currency crises and the breakdown of the U.S. foreign policy consensus over Southeast Asia. Books emerged with titles such as "Retreat From Empire?" and "The End of the American Era." More national malaise followed Watergate and the fall of Saigon. Stage three came in the late 1980s, when a resurgent Japan seemed to be challenging U.S. preeminence in manufacturing and possibly even finance. In 1991, Democratic presidential aspirant Paul Tsongas observed that "the Cold War is over. . . . Germany and Japan won." Well, not quite.

In 2008, we can mark another perilous decade: the tech mania of 1997-2000, morphing into a bubble and market crash; the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks; imperial hubris and the Bush administration's bungled 2003 invasion of Iraq. These were followed by OPEC's abandoning its $22-$28 price range for oil, with the cost per barrel rising over five years to more than $100; the collapse of global respect for the United States over the Iraq war; the imploding U.S. housing market and debt bubble; and the almost 50 percent decline of the U.S. dollar against the euro since 2002. Small wonder a global financial crisis is in the air.

Here, then, is the unnerving possibility: that another, imminent global crisis could make the half-century between the 1970s and the 2020s the equivalent for the United States of what the half-century before 1950 was for Britain. This may well be the Big One: the multi-decade endgame of U.S. ascendancy. The chronology makes historical sense -- four decades of premature jitters segueing into unhappy reality.

The most chilling parallel with the failures of the old powers is the United States' unhealthy reliance on the financial sector as the engine of its growth. In the 18th century, the Dutch thought they could replace their declining industry and physical commerce with grand money-lending schemes to foreign nations and princes. But a series of crashes and bankruptcies in the 1760s and 1770s crippled Holland's economy. In the early 1900s, one apprehensive minister argued that Britain could not thrive as a "hoarder of invested securities" because "banking is not the creator of our prosperity but the creation of it." By the late 1940s, the debt loads of two world wars proved the point, and British global economic leadership became history.

In the United States, the financial services sector passed manufacturing as a component of the GDP in the mid-1990s. But market enthusiasm seems to have blocked any debate over this worrying change: In the 1970s, manufacturing occupied 25 percent of GDP and financial services just 12 percent, but by 2003-06, finance enjoyed 20-21 percent, and manufacturing had shriveled to 12 percent.

The downside is that the final four or five percentage points of financial-sector GDP expansion in the 1990s and 2000s involved mischief and self-dealing: the exotic mortgage boom, the reckless bundling of loans into securities and other innovations better left to casinos. Run-amok credit was the lubricant. Between 1987 and 2007, total debt in the United States jumped from $11 trillion to $48 trillion, and private financial-sector debt led the great binge.

Washington looked kindly on the financial sector throughout the 1980s and 1990s, providing it with endless liquidity flows and bailouts. Inexcusably, movers and shakers such as Greenspan, former treasury secretary Robert Rubin and the current secretary, Henry Paulson, refused to regulate the industry. All seemed to welcome asset bubbles; they may have figured the finance industry to be the new dominant sector of economic evolution, much as industry had replaced agriculture in the late 19th century. But who seriously expects the next great economic power -- China, India, Brazil -- to have a GDP dominated by finance?

With the help of the overgrown U.S. financial sector, the United States of 2008 is the world's leading debtor, has by far the largest current-account deficit and is the leading importer, at great expense, of both manufactured goods and oil. The potential damage if the world soon undergoes the greatest financial crisis since the 1930s is incalculable. The loss of global economic leadership that overtook Britain and Holland seems to be looming on our own horizon.

7.19.2009

Kevin Phillips: Bad Money

Kevin Phillips - Bad Money: the Global Crisis of American Capitalism

FRONTLINE: Breaking the Bank,

In Breaking the Bank, FRONTLINE producer Michael Kirk (Inside the Meltdown, Bush's War) draws on a rare combination of high-profile interviews with key players Ken Lewis and former Merrill Lynch CEO John Thain to reveal the story of two banks at the heart of the financial crisis, the rocky merger, and the government's new role in taking over -- some call it "nationalizing" -- the American banking system.

Watch Frontline's "Breaking the Bank":

It all began on that fateful weekend in September 2008 when the American economy was on the verge of melting down. Then-Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson, his former protégé John Thain, and Ken Lewis, one of the most powerful bankers in the country, secretly cut a deal to merge Bank of America and Merrill Lynch.

The merger of the nation's largest bank and Merrill Lynch was supposed to help save the American financial system by preventing the imminent Lehman Brothers bankruptcy from setting off a destructive chain reaction. But it became immediately clear that it had not worked. Within days, the entire global financial system was collapsing.

Watch Frontline's "Breaking the Bank":

It all began on that fateful weekend in September 2008 when the American economy was on the verge of melting down. Then-Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson, his former protégé John Thain, and Ken Lewis, one of the most powerful bankers in the country, secretly cut a deal to merge Bank of America and Merrill Lynch.

The merger of the nation's largest bank and Merrill Lynch was supposed to help save the American financial system by preventing the imminent Lehman Brothers bankruptcy from setting off a destructive chain reaction. But it became immediately clear that it had not worked. Within days, the entire global financial system was collapsing.

7.18.2009

Bush's House of Cards

Dean Baker correctly predicts the bursting of the housing bubble. In an article entitled, "Bush's House of Cards," published in the Nation Magazine in 2004, Professor Baker outlines the causes and failures of the Bush economy. Why was his voice ignored? I don't know, but this article by Mr. Baker correctly correlates housing prices with rents. Peter Schiff as well as other noted economists and financial gurus also note the increasing housing prices with the rent prices. Dean Baker was yet another, in a long line of smart economists that warned of the financial meltdown, credit crisis and housing market bubble.

Dean Baker correctly predicts the bursting of the housing bubble. In an article entitled, "Bush's House of Cards," published in the Nation Magazine in 2004, Professor Baker outlines the causes and failures of the Bush economy. Why was his voice ignored? I don't know, but this article by Mr. Baker correctly correlates housing prices with rents. Peter Schiff as well as other noted economists and financial gurus also note the increasing housing prices with the rent prices. Dean Baker was yet another, in a long line of smart economists that warned of the financial meltdown, credit crisis and housing market bubble.  Dean Baker writes on August 9, 2004: The latest data on growth suggest that the economy may again be faltering, just when President Bush desperately needs good numbers to make the case for his re-election. As bad as the Bush economic record is, it would be far worse if not for the growth of an unsustainable housing bubble through the three and a half years of the Bush Administration.

Dean Baker writes on August 9, 2004: The latest data on growth suggest that the economy may again be faltering, just when President Bush desperately needs good numbers to make the case for his re-election. As bad as the Bush economic record is, it would be far worse if not for the growth of an unsustainable housing bubble through the three and a half years of the Bush Administration.  The housing market has supported the economy both directly--through construction of new homes and purchases of existing homes--and indirectly, by allowing families to borrow against the increased value of their homes. Housing construction is up more than 17 percent from its level at the end of the recession. Purchases of existing homes hit a record of 6.1 million in 2003, more than 500,000 above the previous record set in 2002. Each home purchase is accompanied by thousands of dollars of closing costs, plus thousands more spent on furniture and remodeling.

The housing market has supported the economy both directly--through construction of new homes and purchases of existing homes--and indirectly, by allowing families to borrow against the increased value of their homes. Housing construction is up more than 17 percent from its level at the end of the recession. Purchases of existing homes hit a record of 6.1 million in 2003, more than 500,000 above the previous record set in 2002. Each home purchase is accompanied by thousands of dollars of closing costs, plus thousands more spent on furniture and remodeling.The indirect impact of the housing bubble is at least as important. Mortgage debt rose by an incredible $2.3 trillion between 2000 and 2003. This borrowing has sustained consumption growth in an environment in which firms have been shedding jobs and cutting back hours, and real wage growth has fallen to zero, although the gains from this elixir are starting to fade with a recent rise in mortgage rates and many families are running out of equity to tap.

The red-hot housing market has forced up home prices nationwide by 35 percent after adjusting for inflation. There is no precedent for this sort of increase in home prices. Historically, home prices have moved at roughly the same pace as the overall rate of inflation. While the bubble has not affected every housing market--in large parts of the country home prices have remained pretty much even with inflation--in the bubble areas, primarily on the two coasts, home prices have exceeded the overall rate of inflation by 60 percentage points or more.

The housing enthusiasts, led by Alan Greenspan, insist that the run-up is not a bubble, but rather reflects fundamental factors in the demand for housing. They cite several factors that could explain the price surge: a limited supply of urban land, immigration increasing the demand for housing, environmental restrictions on building, and rising family income leading to increased demand for housing.

The housing enthusiasts, led by Alan Greenspan, insist that the run-up is not a bubble, but rather reflects fundamental factors in the demand for housing. They cite several factors that could explain the price surge: a limited supply of urban land, immigration increasing the demand for housing, environmental restrictions on building, and rising family income leading to increased demand for housing.

A quick examination shows that none of these explanations holds water. Land is always in limited supply; that fact never led to such a widespread run-up in home prices in the past. Immigration didn't just begin in the late nineties. Also, most recent immigrants are low-wage workers. They are not in the market for the $500,000 homes that middle-class families now occupy in bubble-inflated markets. Furthermore, the demographic impact of recent immigration rates pales compared to the impact of baby boomers first forming their first households in the late seventies and eighties. And that did not lead to a comparable boom in home prices. Environmental restrictions on building, moreover, didn't begin in the late nineties. In fact, in light of the election of the Gingrich Congress in 1994 and subsequent Republican dominance of many state houses, it's unlikely that these restrictions suddenly became more severe at the end of the decade. And the income growth at the end of the nineties, while healthy, was only mediocre compared to the growth seen over the period from 1951 to 1973. In any event, this income growth has petered out in the last two years.

Environmental restrictions on building, moreover, didn't begin in the late nineties. In fact, in light of the election of the Gingrich Congress in 1994 and subsequent Republican dominance of many state houses, it's unlikely that these restrictions suddenly became more severe at the end of the decade. And the income growth at the end of the nineties, while healthy, was only mediocre compared to the growth seen over the period from 1951 to 1973. In any event, this income growth has petered out in the last two years.

Environmental restrictions on building, moreover, didn't begin in the late nineties. In fact, in light of the election of the Gingrich Congress in 1994 and subsequent Republican dominance of many state houses, it's unlikely that these restrictions suddenly became more severe at the end of the decade. And the income growth at the end of the nineties, while healthy, was only mediocre compared to the growth seen over the period from 1951 to 1973. In any event, this income growth has petered out in the last two years.

Environmental restrictions on building, moreover, didn't begin in the late nineties. In fact, in light of the election of the Gingrich Congress in 1994 and subsequent Republican dominance of many state houses, it's unlikely that these restrictions suddenly became more severe at the end of the decade. And the income growth at the end of the nineties, while healthy, was only mediocre compared to the growth seen over the period from 1951 to 1973. In any event, this income growth has petered out in the last two years. The final blow to the argument of the housing enthusiasts is the recent trend in rents. Rental prices did originally follow sale prices upward, although not nearly as fast. However, in the last two years, the pace of rental price increases has slowed under the pressure of record high vacancy rates. In some bubble areas, like Seattle and San Francisco, rents are actually falling. No one can produce an explanation as to how fundamental factors can lead to a run-up in home sale prices, but not rents.

The final blow to the argument of the housing enthusiasts is the recent trend in rents. Rental prices did originally follow sale prices upward, although not nearly as fast. However, in the last two years, the pace of rental price increases has slowed under the pressure of record high vacancy rates. In some bubble areas, like Seattle and San Francisco, rents are actually falling. No one can produce an explanation as to how fundamental factors can lead to a run-up in home sale prices, but not rents.At the end of the day, housing can be viewed like Internet stocks on the NASDAQ. A run-up in prices eventually attracts more supply. This takes the form of IPOs on the NASDAQ, and new homes in the housing market. Eventually, there are not enough people to sustain demand, and prices plunge.

The crash of the housing market will not be pretty. It is virtually certain to lead to a second dip to the recession. Even worse, millions of families will see the bulk of their savings disappear as homes in some of the bubble areas lose 30 percent, or more, of their value. Foreclosures, which are already at near record highs, will almost certainly soar to new peaks. This has happened before in regional markets that had severe housing bubbles, most notably in Colorado and Texas after the collapse of oil prices in the early eighties. However, this time the bubble markets are more the rule than the exception, infecting most of real estate markets on both coasts, as well as many local markets in the center of the country.

The crash of the housing market will not be pretty. It is virtually certain to lead to a second dip to the recession. Even worse, millions of families will see the bulk of their savings disappear as homes in some of the bubble areas lose 30 percent, or more, of their value. Foreclosures, which are already at near record highs, will almost certainly soar to new peaks. This has happened before in regional markets that had severe housing bubbles, most notably in Colorado and Texas after the collapse of oil prices in the early eighties. However, this time the bubble markets are more the rule than the exception, infecting most of real estate markets on both coasts, as well as many local markets in the center of the country.In this context, it's especially disturbing that the Bush administration has announced that it is cutting back Section 8 housing vouchers, which provide rental assistance to low income families, while easing restrictions on mortgage loans. Low-income families will now be able to get subsidized mortgage loans through the Federal Housing Administration that are equal to 103 percent of the purchase price of a home. Home ownership can sometimes be a ticket to the middle class, but buying homes at bubble-inflated prices may saddle hundreds of thousands of poor families with an unmanageable debt burden.

As with the stock bubble, the big question in the housing bubble is when it will burst. No one can give a definitive answer to that one, but Alan Greenspan seems determined to ensure that it will be after November. Instead of warning prospective homebuyers of the risk of buying housing in a bubble-inflated market, Greenspan gave Congressional testimony in the summer of 2002 arguing that there is no such bubble. This is comparable to his issuing a "buy" recommendation for the NASDAQ at the beginning of 1999. More recently, Greenspan has done everything in his power to keep mortgage rates as low as possible, at one point even offering markets the hope that the Fed would take the extraordinary measure of directly buying long-term Treasury bonds. The man who testified that the Bush tax cuts were a good idea apparently has one last job to perform for the President.

As with the stock bubble, the big question in the housing bubble is when it will burst. No one can give a definitive answer to that one, but Alan Greenspan seems determined to ensure that it will be after November. Instead of warning prospective homebuyers of the risk of buying housing in a bubble-inflated market, Greenspan gave Congressional testimony in the summer of 2002 arguing that there is no such bubble. This is comparable to his issuing a "buy" recommendation for the NASDAQ at the beginning of 1999. More recently, Greenspan has done everything in his power to keep mortgage rates as low as possible, at one point even offering markets the hope that the Fed would take the extraordinary measure of directly buying long-term Treasury bonds. The man who testified that the Bush tax cuts were a good idea apparently has one last job to perform for the President.Source: Nation, 4 August 2004, by Dean Baker.

7.17.2009

Goldman Sachs: Pirates of Wall Street

In the New York Times article, "The Joy of Sachs" by Paul Krugman, Mr. Krugman states: The American economy remains in dire straits, with one worker in six unemployed or underemployed. Yet Goldman Sachs just reported record quarterly profits — and it’s preparing to hand out huge bonuses, comparable to what it was paying before the crisis. What does this contrast tell us?

In the New York Times article, "The Joy of Sachs" by Paul Krugman, Mr. Krugman states: The American economy remains in dire straits, with one worker in six unemployed or underemployed. Yet Goldman Sachs just reported record quarterly profits — and it’s preparing to hand out huge bonuses, comparable to what it was paying before the crisis. What does this contrast tell us?First, it tells us that Goldman is very good at what it does. Unfortunately, what it does is bad for America.

Second, it shows that Wall Street’s bad habits — above all, the system of compensation that helped cause the financial crisis — have not gone away.

Third, it shows that by rescuing the financial system without reforming it, Washington has done nothing to protect us from a new crisis, and, in fact, has made another crisis more likely.

Let’s start by talking about how Goldman makes money.

Let’s start by talking about how Goldman makes money.Over the past generation — ever since the banking deregulation of the Reagan years — the U.S. economy has been “financialized.” The business of moving money around, of slicing, dicing and repackaging financial claims, has soared in importance compared with the actual production of useful stuff. The sector officially labeled “securities, commodity contracts and investments” has grown especially fast, from only 0.3 percent of G.D.P. in the late 1970s to 1.7 percent of G.D.P. in 2007.

Such growth would be fine if financialization really delivered on its promises — if financial firms made money by directing capital to its most productive uses, by developing innovative ways to spread and reduce risk. But can anyone, at this point, make those claims with a straight face? Financial firms, we now know, directed vast quantities of capital into the construction of unsellable houses and empty shopping malls. They increased risk rather than reducing it, and concentrated risk rather than spreading it. In effect, the industry was selling dangerous patent medicine to gullible consumers.

Goldman’s role in the financialization of America was similar to that of other players, except for one thing: Goldman didn’t believe its own hype. Other banks invested heavily in the same toxic waste they were selling to the public at large. Goldman, famously, made a lot of money selling securities backed by subprime mortgages — then made a lot more money by selling mortgage-backed securities short, just before their value crashed. All of this was perfectly legal, but the net effect was that Goldman made profits by playing the rest of us for suckers.

And Wall Streeters have every incentive to keep playing that kind of game.

And Wall Streeters have every incentive to keep playing that kind of game.The huge bonuses Goldman will soon hand out show that financial-industry highfliers are still operating under a system of heads they win, tails other people lose. If you’re a banker, and you generate big short-term profits, you get lavishly rewarded — and you don’t have to give the money back if and when those profits turn out to have been a mirage. You have every reason, then, to steer investors into taking risks they don’t understand.

And the events of the past year have skewed those incentives even more, by putting taxpayers as well as investors on the hook if things go wrong.

I won’t try to parse the competing claims about how much direct benefit Goldman received from recent financial bailouts, especially the government’s assumption of A.I.G.’s liabilities. What’s clear is that Wall Street in general, Goldman very much included, benefited hugely from the government’s provision of a financial backstop — an assurance that it will rescue major financial players whenever things go wrong.

You can argue that such rescues are necessary if we’re to avoid a replay of the Great Depression. In fact, I agree. But the result is that the financial system’s liabilities are now backed by an implicit government guarantee.

Now the last time there was a comparable expansion of the financial safety net, the creation of federal deposit insurance in the 1930s, it was accompanied by much tighter regulation, to ensure that banks didn’t abuse their privileges. This time, new regulations are still in the drawing-board stage — and the finance lobby is already fighting against even the most basic protections for consumers.

Now the last time there was a comparable expansion of the financial safety net, the creation of federal deposit insurance in the 1930s, it was accompanied by much tighter regulation, to ensure that banks didn’t abuse their privileges. This time, new regulations are still in the drawing-board stage — and the finance lobby is already fighting against even the most basic protections for consumers.If these lobbying efforts succeed, we’ll have set the stage for an even bigger financial disaster a few years down the road. The next crisis could look something like the savings-and-loan mess of the 1980s, in which deregulated banks gambled with, or in some cases stole, taxpayers’ money — except that it would involve the financial industry as a whole.

The bottom line is that Goldman’s blowout quarter is good news for Goldman and the people who work there. It’s good news for financial superstars in general, whose paychecks are rapidly climbing back to precrisis levels. But it’s bad news for almost everyone else.

The New York Times

Labels:

economy,

Goldman Sachs,

New York Times,

Paul Krugman

7.16.2009

Wall Street Insider's Revolution

March 2009 Democracy Now with Amy Goodman interview with Rolling Stone Magazine, journalist Matt Tabbi takes an in-depth look at the story behind AIG. The reality is that the worldwide economic meltdown and the bailout that followed were together a kind of revolution, a coup détat, writes Taibbi. They cemented and formalized a political trend that has been snowballing for decades: the gradual takeover of the government by a small class of connected insiders, who used money to control elections, buy influence and systematically weaken financial regulations.

Wall Street Insiders Are Using the Bailout to Stage a Revolution-1/2

The Big Takeover

Matt Taibbi reports in the Rolling Stone, in his article entitled, "The Big Takeover" that "the global economic crisis isn't about money - it's about power. How Wall Street insiders are using the bailout to stage a revolution." Mr. Taibbi writes: "It's over — we're officially, royally fucked. No empire can survive being rendered a permanent laughingstock, which is what happened as of a few weeks ago, when the buffoons who have been running things in this country finally went one step too far. It happened when Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner was forced to admit that he was once again going to have to stuff billions of taxpayer dollars into a dying insurance giant called AIG, itself a profound symbol of our national decline — a corporation that got rich insuring the concrete and steel of American industry in the country's heyday, only to destroy itself chasing phantom fortunes at the Wall Street card tables, like a dissolute nobleman gambling away the family estate in the waning days of the British Empire."

Mr. Taibbi writes: "It's over — we're officially, royally fucked. No empire can survive being rendered a permanent laughingstock, which is what happened as of a few weeks ago, when the buffoons who have been running things in this country finally went one step too far. It happened when Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner was forced to admit that he was once again going to have to stuff billions of taxpayer dollars into a dying insurance giant called AIG, itself a profound symbol of our national decline — a corporation that got rich insuring the concrete and steel of American industry in the country's heyday, only to destroy itself chasing phantom fortunes at the Wall Street card tables, like a dissolute nobleman gambling away the family estate in the waning days of the British Empire."

Liddy made AIG sound like an orphan begging in a soup line, hungry and sick from being left out in someone else's financial weather. He conveniently forgot to mention that AIG had spent more than a decade systematically scheming to evade U.S. and international regulators, or that one of the causes of its "pneumonia" was making colossal, world-sinking $500 billion bets with money it didn't have, in a toxic and completely unregulated derivatives market.

Nor did anyone mention that when AIG finally got up from its seat at the Wall Street casino, broke and busted in the afterdawn light, it owed money all over town — and that a huge chunk of your taxpayer dollars in this particular bailout scam will be going to pay off the other high rollers at its table. Or that this was a casino unique among all casinos, one where middle-class taxpayers cover the bets of billionaires. People are pissed off about this financial crisis, and about this bailout, but they're not pissed off enough. The reality is that the worldwide economic meltdown and the bailout that followed were together a kind of revolution, a coup d'état. They cemented and formalized a political trend that has been snowballing for decades: the gradual takeover of the government by a small class of connected insiders, who used money to control elections, buy influence and systematically weaken financial regulations.

People are pissed off about this financial crisis, and about this bailout, but they're not pissed off enough. The reality is that the worldwide economic meltdown and the bailout that followed were together a kind of revolution, a coup d'état. They cemented and formalized a political trend that has been snowballing for decades: the gradual takeover of the government by a small class of connected insiders, who used money to control elections, buy influence and systematically weaken financial regulations.

The crisis was the coup de grâce: Given virtually free rein over the economy, these same insiders first wrecked the financial world, then cunningly granted themselves nearly unlimited emergency powers to clean up their own mess. And so the gambling-addict leaders of companies like AIG end up not penniless and in jail, but with an Alien-style death grip on the Treasury and the Federal Reserve — "our partners in the government," as Liddy put it with a shockingly casual matter-of-factness after the most recent bailout.

The mistake most people make in looking at the financial crisis is thinking of it in terms of money, a habit that might lead you to look at the unfolding mess as a huge bonus-killing downer for the Wall Street class. But if you look at it in purely Machiavellian terms, what you see is a colossal power grab that threatens to turn the federal government into a kind of giant Enron — a huge, impenetrable black box filled with self-dealing insiders whose scheme is the securing of individual profits at the expense of an ocean of unwitting involuntary shareholders, previously known as taxpayers.

Rachel Maddow Show: Matt Taibbi on Why Financial Institutions Should Be Broken Up

Mr. Taibbi writes: "It's over — we're officially, royally fucked. No empire can survive being rendered a permanent laughingstock, which is what happened as of a few weeks ago, when the buffoons who have been running things in this country finally went one step too far. It happened when Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner was forced to admit that he was once again going to have to stuff billions of taxpayer dollars into a dying insurance giant called AIG, itself a profound symbol of our national decline — a corporation that got rich insuring the concrete and steel of American industry in the country's heyday, only to destroy itself chasing phantom fortunes at the Wall Street card tables, like a dissolute nobleman gambling away the family estate in the waning days of the British Empire."

Mr. Taibbi writes: "It's over — we're officially, royally fucked. No empire can survive being rendered a permanent laughingstock, which is what happened as of a few weeks ago, when the buffoons who have been running things in this country finally went one step too far. It happened when Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner was forced to admit that he was once again going to have to stuff billions of taxpayer dollars into a dying insurance giant called AIG, itself a profound symbol of our national decline — a corporation that got rich insuring the concrete and steel of American industry in the country's heyday, only to destroy itself chasing phantom fortunes at the Wall Street card tables, like a dissolute nobleman gambling away the family estate in the waning days of the British Empire."

The latest bailout came as AIG admitted to having just posted the largest quarterly loss in American corporate history — some $61.7 billion. In the final three months of last year, the company lost more than $27 million every hour. That's $465,000 a minute, a yearly income for a median American household every six seconds, roughly $7,750 a second. And all this happened at the end of eight straight years that America devoted to frantically chasing the shadow of a terrorist threat to no avail, eight years spent stopping every citizen at every airport to search every purse, bag, crotch and briefcase for juice boxes and explosive tubes of toothpaste. Yet in the end, our government had no mechanism for searching the balance sheets of companies that held life-or-death power over our society and was unable to spot holes in the national economy the size of Libya (whose entire GDP last year was smaller than AIG's 2008 losses).

So it's time to admit it: We're fools, protagonists in a kind of gruesome comedy about the marriage of greed and stupidity. And the worst part about it is that we're still in denial — we still think this is some kind of unfortunate accident, not something that was created by the group of psychopaths on Wall Street whom we allowed to gang-rape the American Dream. When Geithner announced the new $30 billion bailout, the party line was that poor AIG was just a victim of a lot of shitty luck — bad year for business, you know, what with the financial crisis and all. Edward Liddy, the company's CEO, actually compared it to catching a cold: "The marketplace is a pretty crummy place to be right now," he said. "When the world catches pneumonia, we get it too." In a pathetic attempt at name-dropping, he even whined that AIG was being "consumed by the same issues that are driving house prices down and 401K statements down and Warren Buffet's investment portfolio down."

So it's time to admit it: We're fools, protagonists in a kind of gruesome comedy about the marriage of greed and stupidity. And the worst part about it is that we're still in denial — we still think this is some kind of unfortunate accident, not something that was created by the group of psychopaths on Wall Street whom we allowed to gang-rape the American Dream. When Geithner announced the new $30 billion bailout, the party line was that poor AIG was just a victim of a lot of shitty luck — bad year for business, you know, what with the financial crisis and all. Edward Liddy, the company's CEO, actually compared it to catching a cold: "The marketplace is a pretty crummy place to be right now," he said. "When the world catches pneumonia, we get it too." In a pathetic attempt at name-dropping, he even whined that AIG was being "consumed by the same issues that are driving house prices down and 401K statements down and Warren Buffet's investment portfolio down."

Liddy made AIG sound like an orphan begging in a soup line, hungry and sick from being left out in someone else's financial weather. He conveniently forgot to mention that AIG had spent more than a decade systematically scheming to evade U.S. and international regulators, or that one of the causes of its "pneumonia" was making colossal, world-sinking $500 billion bets with money it didn't have, in a toxic and completely unregulated derivatives market.

Nor did anyone mention that when AIG finally got up from its seat at the Wall Street casino, broke and busted in the afterdawn light, it owed money all over town — and that a huge chunk of your taxpayer dollars in this particular bailout scam will be going to pay off the other high rollers at its table. Or that this was a casino unique among all casinos, one where middle-class taxpayers cover the bets of billionaires.

People are pissed off about this financial crisis, and about this bailout, but they're not pissed off enough. The reality is that the worldwide economic meltdown and the bailout that followed were together a kind of revolution, a coup d'état. They cemented and formalized a political trend that has been snowballing for decades: the gradual takeover of the government by a small class of connected insiders, who used money to control elections, buy influence and systematically weaken financial regulations.

People are pissed off about this financial crisis, and about this bailout, but they're not pissed off enough. The reality is that the worldwide economic meltdown and the bailout that followed were together a kind of revolution, a coup d'état. They cemented and formalized a political trend that has been snowballing for decades: the gradual takeover of the government by a small class of connected insiders, who used money to control elections, buy influence and systematically weaken financial regulations.The crisis was the coup de grâce: Given virtually free rein over the economy, these same insiders first wrecked the financial world, then cunningly granted themselves nearly unlimited emergency powers to clean up their own mess. And so the gambling-addict leaders of companies like AIG end up not penniless and in jail, but with an Alien-style death grip on the Treasury and the Federal Reserve — "our partners in the government," as Liddy put it with a shockingly casual matter-of-factness after the most recent bailout.